“PILLARS” is Generative Art, art created by code. But what does programming have to do with art? Well, a lot actually. In this blog article, we will explore the unique advantages that programming can bring to art & design.

“PILLARS” is Generative Art, art created by code. But what does programming have to do with art? Well, a lot actually. In this blog article, we will explore the unique advantages that programming can bring to art & design.

PRECISION, ORDER, AND SCALE

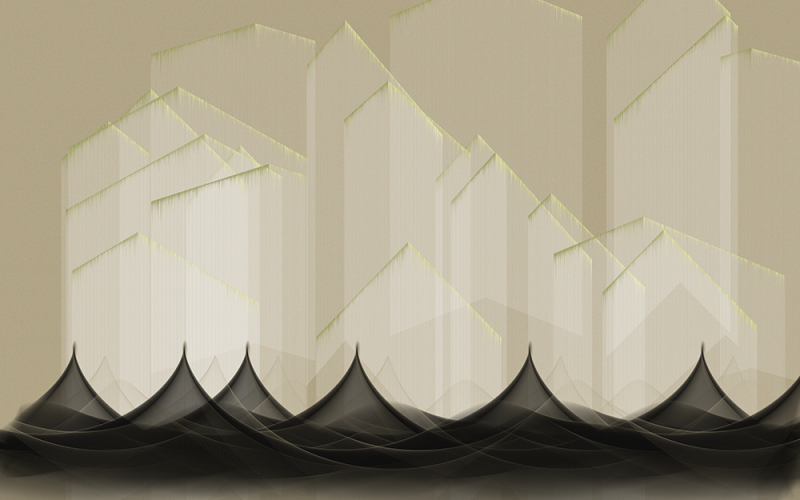

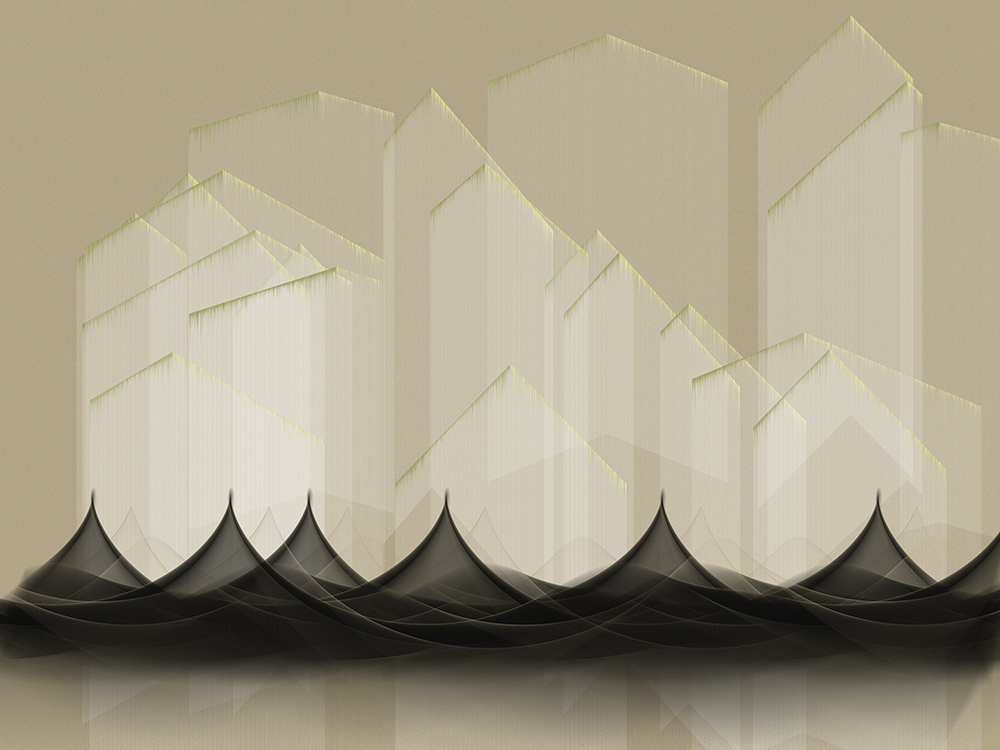

In PILLARS, countless thousands of precise lines are drawn seconds after you run the program, but ORDER in generative art is not limited to lines or geometric shapes. For instance, the mountainous waves at the bottom of the canvas are actually generated from straight lines. Furthermore, programs can use abstraction to create complexity that is non-linear and not confined to a single scale. In other artwork, this might produce networks of shapes, tangles of curves, or textures unseen in nature.

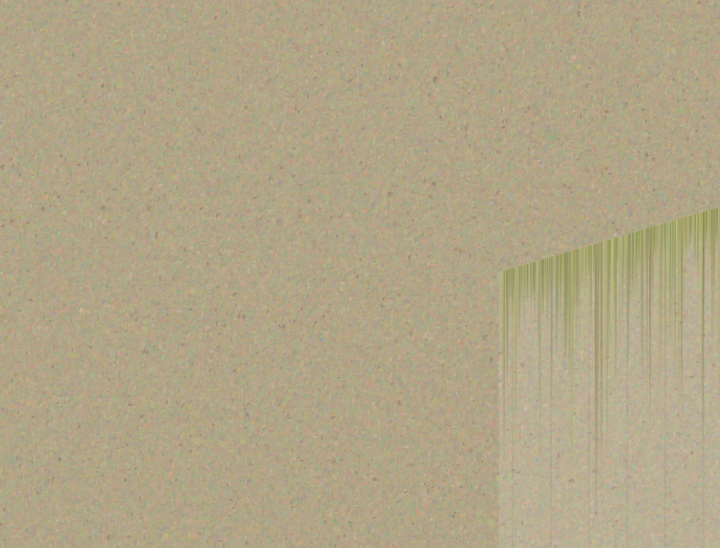

*Close-up of PILLARS background*

The background of PILLARS is not an image. Instead, the paper-like-look is generated through millions of slightly off-colored circles that create the impression of roughness and irregularity. Since PILLARS is a 48 million pixel image, doing this kind of work by hand would be extremely impractical. With algorithmic art, precision over scale is commonplace. This allows the artist to take a fundamentally different approach to textures and shapes, and the results can be both alien and fascinating. RANDOMNESS, PARAMETERIZATION, and RECURSION If you look closely, you will see that the background paper-texture of PILLARS is actually random. Randomness helps to ensure variety at scale, while maintaining a sense of unity. However, random-ness doesn’t always result in uniform noise that smooths out as you move farther away. For example, the etched lines at the top of the building-like pillars in this image are “modulated randomness”, where by the lines random length looks more like a wave function when far away, and more like random noise as you look closely. Randomness thus allows you to set the scale for which we look for patterns, to usher the eye closer into the image, or farther away.

Algorithmic artwork also gives the artist precision over randomness. For example, the building-like pillars are in random positions, but they are limited to a certain range to set them ‘above’ the mountain waves below. The buildings are drawn with a function, drawBuild(), which is “parametrized” to random x y positions. Thus, order and randomness intermix so that each building is both similar and different from every other. Indeed, with this combination of parametrization and randomness, a single program generate an entire series of images, each with completely different aesthetics, textures, and meaning. Simple parameters may include lengths of shapes, colors, thicknesses of lines, and angles of rotation. This allows students to combine both mathematical concepts like trigonometry (sin,cos) with their own functions, sprites, and shapes.

For example, the etched lines at the top of the building-like pillars in this image are “modulated randomness”, where by the lines random length looks more like a wave function when far away, and more like random noise as you look closely. Randomness thus allows you to set the scale for which we look for patterns, to usher the eye closer into the image, or farther away.

Algorithmic artwork also gives the artist precision over randomness. For example, the building-like pillars are in random positions, but they are limited to a certain range to set them ‘above’ the mountain waves below. The buildings are drawn with a function, drawBuild(), which is “parametrized” to random x y positions. Thus, order and randomness intermix so that each building is both similar and different from every other. Indeed, with this combination of parametrization and randomness, a single program generate an entire series of images, each with completely different aesthetics, textures, and meaning. Simple parameters may include lengths of shapes, colors, thicknesses of lines, and angles of rotation. This allows students to combine both mathematical concepts like trigonometry (sin,cos) with their own functions, sprites, and shapes.

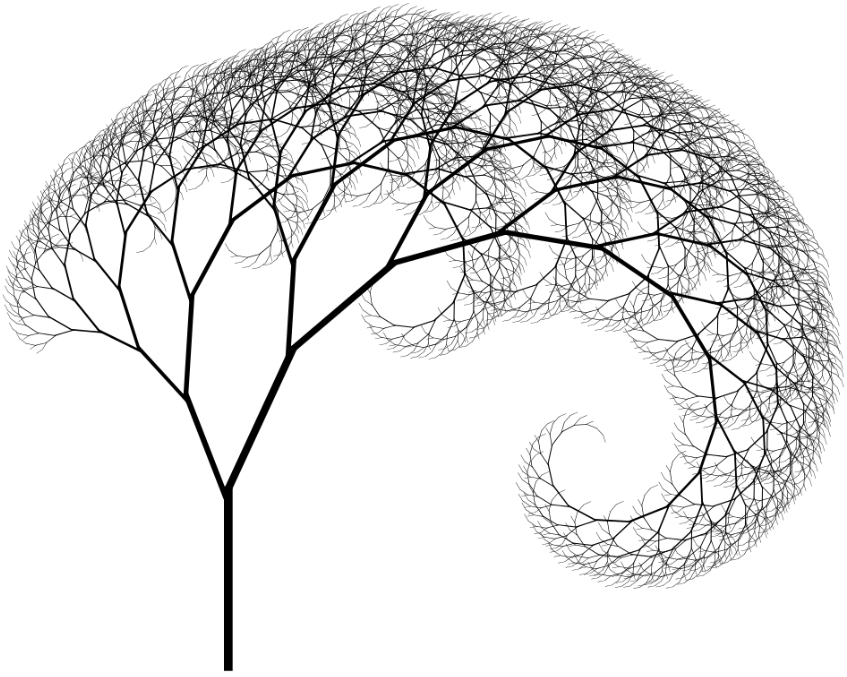

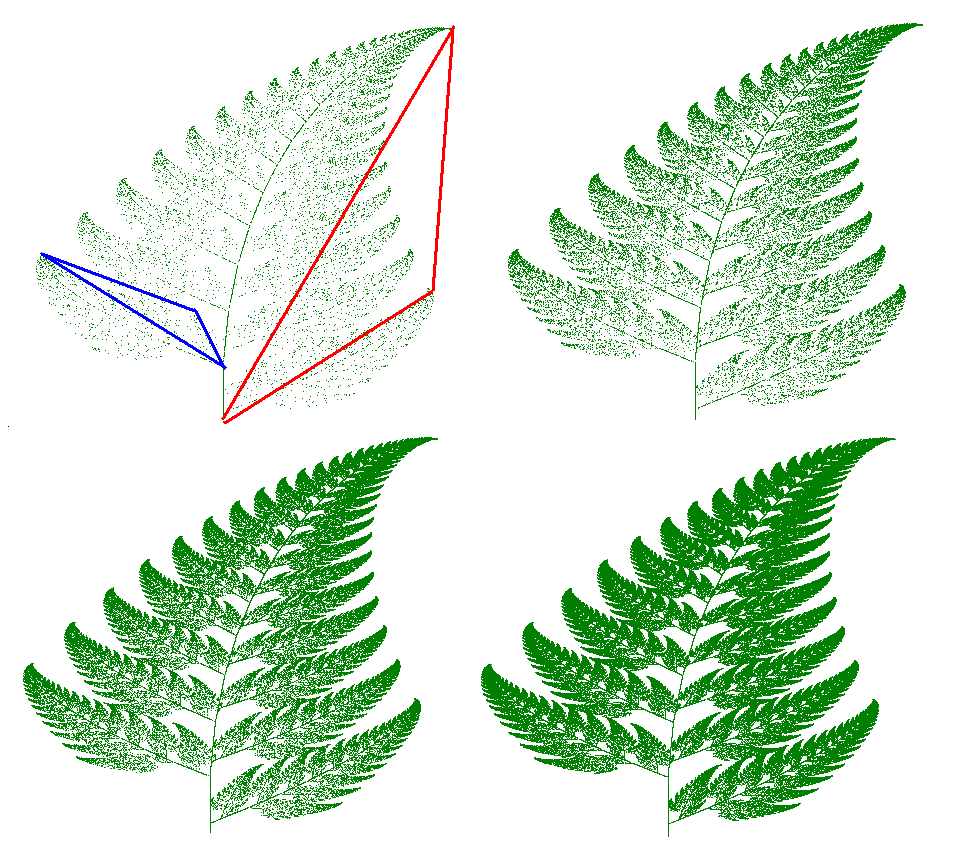

This idea of parameterization can be extended even deeper to create shapes that look perfectly natural. For example, trees where branches randomly break off from earlier branches, or snow flakes that crystallize in random directions from a solid core. Although these concepts are not shown in PILLARS, you might find it interesting to search for ‘recursive art’ as well as ‘fractals‘. By using parameterization and randomness to draw at all scales, you can create seemingly infinite complexity both small and large from very few lines of code.

PHYSICS, BIOLOGY, and NATURE

In PILLARS, the majestic curves of the dune mountains draw up thoughts of ancient ruins, and the streaking lines at the top conjure up images of limestone deposits or acid rain decay. Combined with the earthy tones and overwhelming scale and majesty, one is left with a sense of overwhelming time and space. Is it curious, that these physical attributes seem to be taken from simple algorithms?

This idea of parameterization can be extended even deeper to create shapes that look perfectly natural. For example, trees where branches randomly break off from earlier branches, or snow flakes that crystallize in random directions from a solid core. Although these concepts are not shown in PILLARS, you might find it interesting to search for ‘recursive art’ as well as ‘fractals‘. By using parameterization and randomness to draw at all scales, you can create seemingly infinite complexity both small and large from very few lines of code.

PHYSICS, BIOLOGY, and NATURE

In PILLARS, the majestic curves of the dune mountains draw up thoughts of ancient ruins, and the streaking lines at the top conjure up images of limestone deposits or acid rain decay. Combined with the earthy tones and overwhelming scale and majesty, one is left with a sense of overwhelming time and space. Is it curious, that these physical attributes seem to be taken from simple algorithms?

Well, actually, it’s not that surprising. Programs are naturally good at simulating the effects of both physical and biological systems. As discussed before, fractal structures that repeat themselves, like veins in an animal, or curves in a sea shell, or ravines around in a wandering river – they all form due to laws of nature. These laws include things such as the ‘square cube law’ that dictates how organisms organize their skin and veins, or newton’s laws that govern the movement of small and large bodies, or laws of viscosity and fluid dynamics that alter currents and eddies of liquids and gases. Algorithmic art is uniquely capable of adding texture on top of equations that mimic the awesome powers of nature, big and small.

Well, actually, it’s not that surprising. Programs are naturally good at simulating the effects of both physical and biological systems. As discussed before, fractal structures that repeat themselves, like veins in an animal, or curves in a sea shell, or ravines around in a wandering river – they all form due to laws of nature. These laws include things such as the ‘square cube law’ that dictates how organisms organize their skin and veins, or newton’s laws that govern the movement of small and large bodies, or laws of viscosity and fluid dynamics that alter currents and eddies of liquids and gases. Algorithmic art is uniquely capable of adding texture on top of equations that mimic the awesome powers of nature, big and small.

You can contrast the generative art of PILLARS with the surreal dream like images generated from “Generative Adversarial Networks” like “DeepDream”. Deep Dream shocks us by being so humanly recognizable while being so obviously not real. This is because it’s a top-down approach that attempts to model high level ideas like objects, scenery, and feelings (“sentiment”) into a large image. Contrast this with the bottoms-up approach of PILLARS where tiny laws of nature build up into something that feels so alien yet also so real. Computers are therefore increasingly close to touching the human experience, at our neural level, as well as our intuitive level.

ITERATION, REUSE, AND DESIGN

PILLARS and other art on KTBYTE.COM is open source, and thus they are particularly easy to alter. This makes them easy for re-working, in contrast to other media, such as pencil, ink, and paint. Even digital artwork done in Photoshop can be difficult to alter, as one small change may not map to other areas of the image, resulting in significant manual effort to change. With algorithmic artwork, thousands of fine details or large sections of the image may be tweaked with only a few lines of code.

This gives art a low cost of failure. Students are encouraged to combine, share, and split existing projects into works of their own. With art, expression is not about finding the right solution to a problem, and so students reuse color schemes, composition strategies, techniques, textures, subjects, and much more. These help to create a visual vocabulary that corresponds to the code. Students don’t need to solve problems over and over, allowing them to focus on higher level ideas.

Finally, this gives students an access to real world design concepts. Although many of these pieces of art are purely aesthetic, the concepts students use can easily be brought over to interaction design, data visualization, or human computer interaction. Where here students may draw random lengths, these lengths could be modified to represent data values from a file, or input from a user. Areas that focus the human attention can become areas of interaction, where users are expected to click, drag, touch, or type in. Parameterization can be based off of data structures built upon a simulation, a game, or whatever a student programmer wants.

CONCLUSION

As we’ve seen, the programmatic approach fundamentally changes the artistic process in ways that the artist cannot ignore.

You can contrast the generative art of PILLARS with the surreal dream like images generated from “Generative Adversarial Networks” like “DeepDream”. Deep Dream shocks us by being so humanly recognizable while being so obviously not real. This is because it’s a top-down approach that attempts to model high level ideas like objects, scenery, and feelings (“sentiment”) into a large image. Contrast this with the bottoms-up approach of PILLARS where tiny laws of nature build up into something that feels so alien yet also so real. Computers are therefore increasingly close to touching the human experience, at our neural level, as well as our intuitive level.

ITERATION, REUSE, AND DESIGN

PILLARS and other art on KTBYTE.COM is open source, and thus they are particularly easy to alter. This makes them easy for re-working, in contrast to other media, such as pencil, ink, and paint. Even digital artwork done in Photoshop can be difficult to alter, as one small change may not map to other areas of the image, resulting in significant manual effort to change. With algorithmic artwork, thousands of fine details or large sections of the image may be tweaked with only a few lines of code.

This gives art a low cost of failure. Students are encouraged to combine, share, and split existing projects into works of their own. With art, expression is not about finding the right solution to a problem, and so students reuse color schemes, composition strategies, techniques, textures, subjects, and much more. These help to create a visual vocabulary that corresponds to the code. Students don’t need to solve problems over and over, allowing them to focus on higher level ideas.

Finally, this gives students an access to real world design concepts. Although many of these pieces of art are purely aesthetic, the concepts students use can easily be brought over to interaction design, data visualization, or human computer interaction. Where here students may draw random lengths, these lengths could be modified to represent data values from a file, or input from a user. Areas that focus the human attention can become areas of interaction, where users are expected to click, drag, touch, or type in. Parameterization can be based off of data structures built upon a simulation, a game, or whatever a student programmer wants.

CONCLUSION

As we’ve seen, the programmatic approach fundamentally changes the artistic process in ways that the artist cannot ignore.